"My instincts were telling me that something's wrong. Something's not right," Jena Scurry testified Monday. "I don't know what, but something wasn't right."

The first witness in Derek Chauvin's murder trial, a 911 dispatcher, testified Monday that she alerted a police supervisor last May 25 after she watched Minneapolis police officers pin George Floyd to the ground live in a security video.

The dispatcher, Jena Scurry, said it was a "gut instinct" that led her to call a police sergeant who was a supervisor for the officers at the scene. She said she glanced up at wall-mounted dispatch screens between taking other calls and saw a police squad car moving back and forth outside Cup Foods, a convenience store. An employee at Cup Foods had called police alleging that Floyd had tried to pass a counterfeit $20 bill.

Scurry said that her job is primarily to listen and that it is rare for a dispatcher to witness an incident in which police are at a scene. She said she has observed police at a scene only three or four times in her seven-year career.

Scurry said the police officers restrained Floyd for so long that she asked someone whether her "screens had frozen because it hadn't changed" and "was told that it was not frozen."

Scurry was one of three witnesses to testify Monday. The two other witnesses were bystanders, Alisha Oyler, who was working at a Speedway station across the street, and Donald Williams II, who had been on his way to Cup Foods. Williams will return to the witness stand when the trial resumes Tuesday.

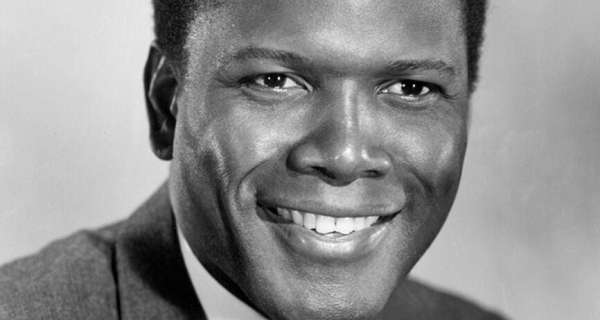

Witness Jena Scurry answers questions during the trial of former Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin at the Hennepin County Courthouse in Minneapolis on Monday.Court TV / via AP Pool

Scurry said May 25 was the first time she had contacted a supervisor about such circumstances. Prosecutor Jerry Blackwell said in his opening statement that after Scurry saw video of Floyd's arrest, "she did something that she had never done in her career: She called the police on the police."

She said that once she observed people moving in the video, she grew concerned that "something may be wrong."

"My instincts were telling me that something's wrong. Something's not right," Scurry told Assistant Minnesota Attorney General Matthew Frank. "I don't know what, but something wasn't right."

She said that she did not know exactly how long the restraint lasted but that it was an extended period of time. Frank asked Scurry to watch the video of Floyd's arrest and explain what parts she had seen. A recording of Scurry's call to the sergeant was also played.

"I don't know, you can call me a snitch if you want to," she told the supervisor, according to audio of the call. "I don't know if they had used force or not. They got something out of the back of the squad, and all of them sat on this man."

During cross-examination, Chauvin's attorney, Eric Nelson, asked Scurry to point out where in the video she could see the squad car moving back and forth.

In opening statements, Blackwell told the jury that the number to remember was 9 minutes, 29 seconds — the amount of time Chauvin knelt on Floyd's neck. Less than an hour into the trial, prosecutors played a bystander's video of Chauvin holding his knee on Floyd's neck.

"My stomach hurts. My neck hurts. Everything hurts," Floyd says. He also tells Chauvin: "I can't breathe, officer." The phrase "I can't breathe" became a rallying cry for activists and protesters around the world after Floyd's death.

Onlookers can be heard repeatedly shouting at the officers to get off Floyd, who was Black. One man said: "You got him down. Let him breathe at least."

A woman, identifying herself as a city Fire Department employee, shouts at Chauvin to check Floyd's pulse.

Chauvin, who is white, "didn't let up" and "didn't get up," even after Floyd, who was handcuffed, said 27 times that he could not breathe and went motionless, Blackwell said.

Chauvin is charged with unintentional second-degree murder, third-degree murder and manslaughter. He and the three other Minneapolis police officers who were at the scene were fired a day after Floyd's death.

"He put his knees upon his neck and his back, grinding and crushing him, until the very breath, no, ladies and gentlemen, until the very life was squeezed out of him," Blackwell said.

Blackwell said that Floyd did not die from a heart attack or an opioid overdose, as the defense has claimed, and that the county medical examiner, who is scheduled to testify, found no evidence of heart injury. The state said it plans to call a forensic pathologist, a pulmonologist, a cardiologist and a toxicologist as witnesses, as well as doctors who specialize in critical care, emergency medicine and internal medicine. The state will also seek testimony from experts — including Police Chief Medaria Arradondo — who will testify that Chauvin used lethal or excessive force against Floyd.

Nelson, Chauvin's attorney, said in his opening statement that the "case is clearly about more than 9 minutes and 29 seconds" and that there are more than 50,000 items in evidence. He also referred to "reasonable doubt," saying, "At the end of this case, we are going to spend a lot of time talking about doubt."

"There is no political or social cause in this courtroom," Nelson said.

Nelson said Floyd resisted arrest and ingested drugs to conceal them from police. Chauvin arrived to assist other officers who were "struggling" to get Floyd into a squad car as the crowd around them grew larger and angrier, Nelson said.

"You will learn Derek Chauvin did exactly what he had been trained to do over the course of his 19-year career," Nelson said. "The use of force is not attractive, but it is a necessary component of policing."

The second witness, Oyler, 23, was questioned by Steve Schleicher, another of the prosecution's outside lawyers, who, like Blackwell, is working pro bono. Oyler recorded a series of brief videos of Floyd's arrest while working at a gas station across the street. Oyler testified that she voluntarily turned the videos over to police. She told Schleicher that she recorded the videos because police are "always messing with people ... and it's not right."

By Janelle Griffith

Janelle Griffith is a national reporter for NBC News focusing on issues of race and policing.

0 Comments